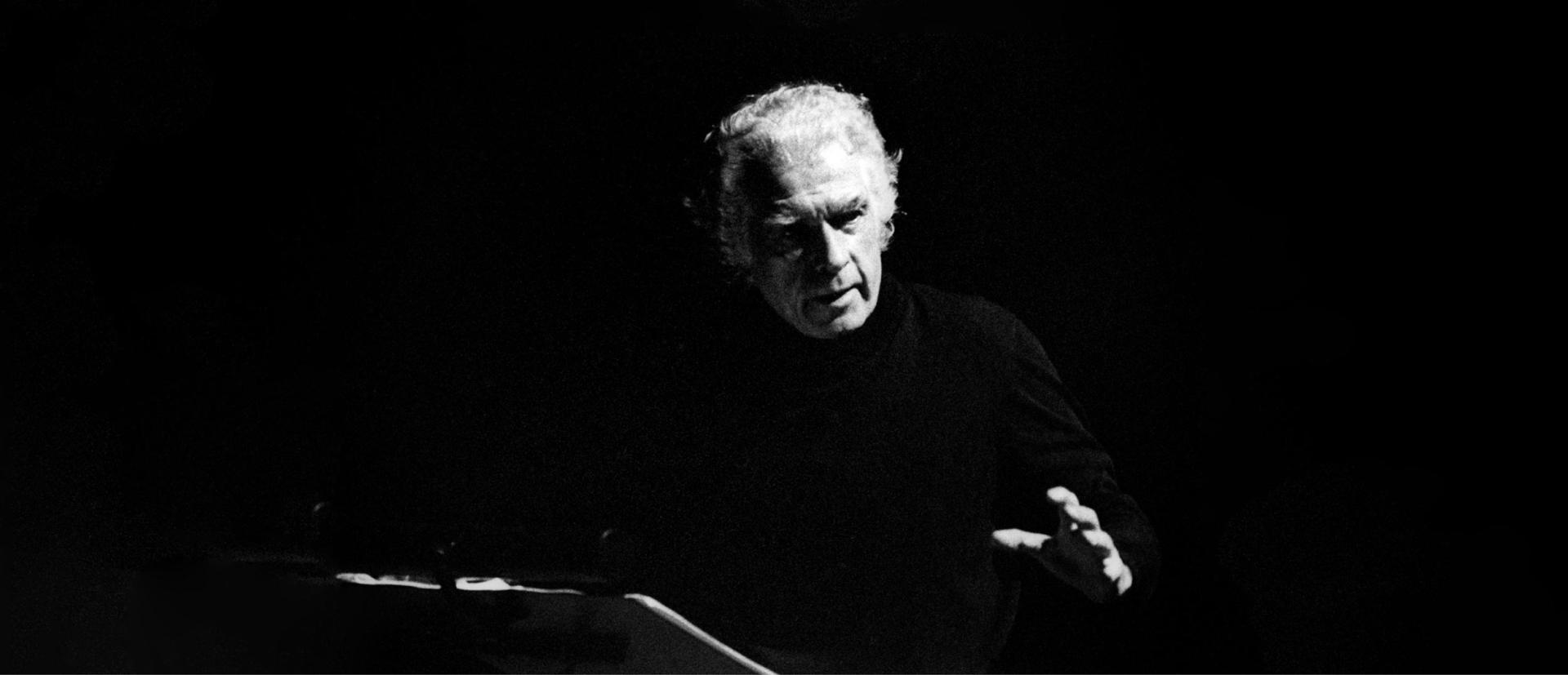

Giorgio Strehler

Giorgio Strehler (Barcola, Trieste 1921- Lugano 1997) director and actor

Giorgio Strehler, also known as “the Director” with a capital “D”, in much the same way as he himself wrote about and thought of Theatre: as a hyperbolic challenge, a diorama, a stage on which an image of the world takes shape, where the great masters of theatre, owners by right, delicately dialogue with the population of characters and, through them, with the audience. Parallel to this “regal” way of seeing theatre which crowned him the true heir to Max Reinhardt (the last of the demiurge directors, who he had admired since he was a child), Strehler had always courted a more severe, almost Jansenistic approach, embodied in the tradition of Copeau and Jouvet, where the director – this time without the capital “D”, but no less important – began from the premise that everything is written in the text and that all that has been previously said and written can be mediated and personified by the Actor (with a capital “A”). These two ways of seeing the role of director are perfectly evident in two of his last works, namely Faust Frammenti, on which he worked continuously between 1988 and 1991, and in which he also starred in the title role, and Elvira o La Passione Teatrale (1987). These directorial concepts were also developed thanks to his family ancestry.

Strehler was born in Barcola, a little town close to Trieste, into a family where languages and cultures mingled. His grandfather was a musician (Giorgio studied music and orchestral conduction as well) and his surname was Lovric; Strehler’s grandmother was French and her surname was Firmy, the surname her grandson took during his Swiss exile, during which he began directing his first productions. His father, Bruno, died very young, when Strehler was little more than two years old. His mother, Alberta, was an acclaimed violinist. The young Strehler grew up in an artistically ‘predestined’ atmosphere and in an environment with a strong female presence. This immersion in femininity was useful to him useful later in life when, as a director, he delineated his female protagonists: Strehler was unparalleled in making the mystery, charm and the deceitful silence of his heroines palpable.

When he was a young boy, he moved to Milan with his mother, where he attended first the Longone boarding school, then the Parini high school, and finally University, where he studied Law. From adolescence, parallel to his studies, he began cultivating a love for the theatre and, as the legend goes, even attended shows as a claqueur. He enrolled in the Milanese Amateur Theatre Academy, where he met his favourite maestro, Gualtiero Tumiati. His first trials outside the school were as an actor, as part of the group Palcoscenico di Posizione in Novara and also at the Triennale, performing in a piece by Ernesto Treccani. But at the tender age of twenty-two, he had already developed the belief that Italian theatre, dominated at the time by Hungarians and false doctors, needed the healthy and demiurgic jolt of a director. He wrote as such in his article: ‘Responsabilità della regia’ (The Responsibility of Directing) in 1942 whilst working for “Posizione”, an article which, despite its absoluteness typical of the era, is fundamental in understanding the Strehler that was to come. Tied by a very strong bond of friendship to Paolo Grassi, who he had met (as the two always maintained) at the stop of the number 6 tram on the corner of Via Petrella, direction Loreto-Duomo, Strehler during the period before the war was straining at the leash and became part of the underground opposition within the GUF (Fascist university groups). Italy’s entry into the war saw him in Switzerland, first as a soldier and then as a refugee in camp Murren, where he forged a friendship with, amongst others, the playwright and director Franco Brusati. Here, very poor but very skilful at using difficulties to his advantage, he managed – under the name Georges Firmy – to find the money to stage, between 1942 and 1945, Murder in the Cathedral by T.S. Eliot, Caligula by A. Camus and Our Town by T. Wilder. At the end of the war, Strehler returned to Italy, determined by then to become a director. His first show, after having ‘directed’ a group of camels for the Liberation day celebrations at the Castello Sforzesco, was Mourning Becomes Electra by O’Neill, with Memo Benassi and Diana Torrieri. He also directed a series of productions for famous companies without particular enthusiasm, and returned to acting in Camus’s Caligula, a production that often had in the audience another great master of the stage, Luchino Visconti. In Caligula, he directed Renzo Ricci and played the role of Scipione himself. In the meantime he also worked as a theatrical critic for “Momento Sera”, never however losing sight of his dream of creating from scratch a different type of theatre.

His chance came with the foundation in 1947 of the Piccolo Teatro della Città di Milano: the first public Italian repertory theatre, which raised its curtains for the first time on the 14th May with the staging of Gorky’s The Lower Depths, in which Strehler played the role of the cobbler Alijosa. This play, which also brought together a considerable part of the company that would for some years be resident at the Piccolo with stars such as Gianni Santuccio, Lilla Brignone and Marcello Moretti, had in a way been “anticipated” the year before, through the staging of Gorky’s The Petty Bourgeois at the Excelsior, directed by Strehler and organised by Paolo Grassi. The foundation of the Piccolo also coincided with the first opera ever to be directed by Strehler, a production of La Traviata at La Scala which was destined to leave its mark.

Since 1947, however, the majority of Strehler’s efforts (first as resident director, later as artistic director, finally as the sole director of the theatre) were essentially devoted to the Piccolo Teatro, where he directed shows that have in the meantime become part of the theatre’s history and of the history of directing. Within this story, which can be described as positively eclectic, there is a constant theme: an interest in all aspects of mankind. This interest, which Strehler pursued throughout his life, was an act of loyalty to the profound reasons for existence harboured by Satin, one of the protagonists of The Lower Depths, namely that “Everything is in man”. Via this placing of mankind under the magnifying glass of his theatre, we see many of the relationships that interested him brought to light: the relationship between man and society, man and himself, man and history, and man and politics. Choices which were in turn reflected by his predilection for certain key authors, veritable companions during the theatrical work of the great Maestro (or better still “Maestro. Period.”, as he is often referred to): Shakespeare, above all others, but also Goldoni, Pirandello, as well as the bourgeois playwrights, the popular national theatre of Bertolazzi, Chekhov and, in his earlier years, contemporary drama; Brecht revealed to him a different approach to the theatre and to acting, an “Italian approach” to the alienation effect.

Although the over two hundred productions Strehler directed cannot all be mentioned, several fundamental shows, linked to key authors, stand out: Richard II (1948), Julius Caesar (1953), Coriolanus (1957), Il gioco dei potenti [Translator’s Note: based on Henry VI] (1965), King Lear (1972) and The Tempest (1978) for Shakespeare; for Goldoni, Harlequin [TN: the full title of the show is Harlequin, Servant of Two Masters] (in all of its versions from 1947 onwards), which hold the record as the longest running and the most seen Italian production in the world, The Holiday Trilogy (1954), The Chioggia Scuffles (1964) and The little square (1975); for Chekhov, Platonov (1959) and The Cherry Orchard (1955 and 1974); for Pirandello, the different editions of The Mountain Giants (1947, 1966, 1994) and As You Desire Me (1988); for Bertolazzi, El nost Milan (1955 and 1979) and L'egoista (1960); for the bourgeois playwrights, Garcia Lorca’s The House of Bernarda Alba (1955) and, above all, Strindberg’s The Storm (1980); for contemporary drama, Dürrenmatt’s The Visit (1960) and Eduardo De Filippo’s Grand Magic (1985); and finally, for Brecht, The Threepenny Opera (1956), The Good Person of Szechwan (1958, 1981 and 1996), Saint Joan of the Stockyards (1970) and most of all, Life of Galileo (1963). However, what comes to the forefront of this amazing theatrical production is his work on the signs of the theatre (the sets, the atmosphere, the unparalleled lighting, the prodigious ability of knowing how to recreate incredibly poetical situations with apparent ease), and his demanding, hard, insatiable investigation on acting. This reached its peak with the veritable fights he got into with his actors: an authentic example of maieutics, and, for those lucky enough to have been present at his rehearsals, the epiphany of a theatrical method.

Strehler’s story, marked by the opening and closing of the theatre’s curtains, took place mostly at the Piccolo Teatro, but not only: in 1968 he abandoned Via Rovello to found his own group, the Teatro Azione, organised on a cooperative basis; with this group he presented P. Weiss’s The Song of the Lusitanian Bogey (1969), a show that anticipated a conceptually ‘poor’ theatre. Saint Joan of the Stockyards (1970) marked his return ‘home’. In addition to this, Strehler also directed the newly created Theatres of Europe, an organisation wished for by Jack Lang and François Mitterrand, in Paris. Indeed, his cursus honorum is extensive: member of the European Parliament, Senator of the Republic and recipient of a long list of honours, including the beloved Legion of Honour. However, his final years were marked by the bitterness caused by a trial, at the end of which he was found not guilty.

He died on Christmas night 1997; his ashes rest in the cemetery of Sant’Anna in Trieste, in the very simple family tomb.

Strehler’s directorial contributions in the field of opera were remarkable, favoured by his musical knowledge and his “ability to rejuvenate the inseparable and traditional gestures of the singers”. Amongst the many productions he conceived, memorable is his participation in the International Festival of Contemporary Music in Venice (Lulu by A. Berg, 1949; La favola del figlio cambiato by G.F. Malipiero, 1952; The Fiery Angel by S. Prokof'ev, 1955), his productions at the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino (Fidelio by Beethoven, 1969) and at the Teatro alla Scala (as far back as the spring of 1946 with Joan of Arc at the Stake by A. Honegger, with Sarah Ferrati), as well as the aforementioned La Traviata, Simon Boccanegra (1971), Macbeth (1975) and Falstaff (1980) by Verdi; the production of the highly praised Cavalleria rusticana by Mascagni, directed by Karajan (1966); at the Piccola Scala with L'histoire du soldat by I. Stravinskij (1957), Un cappello di paglia di Firenze by N. Rota (1958) and The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny by K. Weill (1964). In addition, he worked on his beloved Mozart: at the Salzburg Festival with The Abduction from the Seraglio (1965) and The Magic Flute (1974), in Paris with The Marriage of Figaro (1973), at La Scala with Don Giovanni (1987) and the sweet lightness of Così fan tutte, an ode to love and youth. More than a testament, this production was a bridge (albeit still “hidden by scaffolding”, due to Strehler’s sudden death a few days prior to the show’s premiere), connecting his fifty years of work with the new Century (for the Milanese theatre in its new venue and for those who have survived him and can reach him only through memories).

Maria Grazia Gregori, from DIZIONARIO DELLO SPETTACOLO del '900, Baldini& Castoldi, Milan 1998